Material Properties and Engineering vs True Stress & Strain

- Engineering

- Nov 30, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 30, 2021

A material property can be defined as a specific characteristic in reaction to a certain stimulus.

These properties differ between materials, but generally materials can be grouped into one of four types, based on their properties and structure:

Metals & Alloys

Ferrous Metals, such as steels and cast irons

Non-ferrous metals, such as copper, aluminium, tungsten and titanium

Plastics

Thermoplastics, such as polythene, polypropylene, acrylics, nylons and PVC

Thermosets, such as polyimides, phenolics and epoxies

Elastomers, such as rubbers, silicones and polyurethanes

Ceramics & Glasses

These include oxides, nitrates, carbides, diamond and graphite

Composites

Polymer, metal, and ceramic matrices

Basic Properties

Strength

A material’s ability to carry loads without deforming

Young’s Modulus

A material's ability to resist deformation under tensile or compressive loading

Stiffness and ductility are not material properties, as they are geometry-dependent

Hardness

A material's ability to resist wear, scratching or indentation

Fatigue Strength

A material's ability to resist deformation caused by repeated (often cyclical) loading

Creep Strength

A material’s ability to resist deformation caused by a constant and unchanging load over a prolonged period of time

Toughness

A material’s ability to resist fracturing

Chemical Properties

These are also important material properties, and include

Density

Specific Heat Capacity

Corrosion Resistance

Flammability

Toxicity

Material Selection Factors

These are not properties as such, but are also important factors to consider when selecting a material for a given purpose:

Processability

Cost

Availability

Sustainability

Engineering Stress & Strain

The majority of the properties listed above can be worked out from the stress-strain relationship of a material. Therefore, a tensile test is one of the most important procedures carried out in the study of materials.

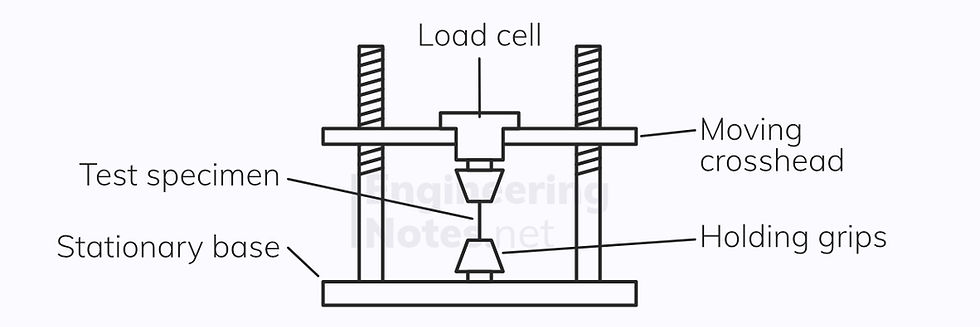

Tensile Test

A test specimen is loaded into a test machine

The moving crosshead slowly moves up or down, to apply a compressive or tensile load – the magnitude of this force is measured by the load cell

An extensometer measures the extension/compression in the test specimen

From the values of force applied and extension, engineering stress, σ, and engineering strain, ε are calculated:

F is the force applied

A is the cross-sectional area of the test specimen

x is the extension

l is the original length of the specimen

Engineering stress and strain are obtained from a tensile test and are sometimes called nominal stress and strain

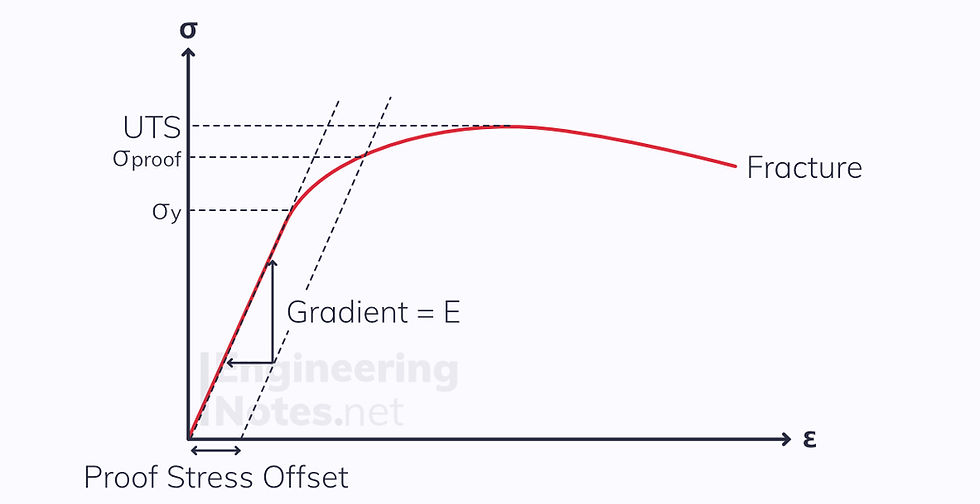

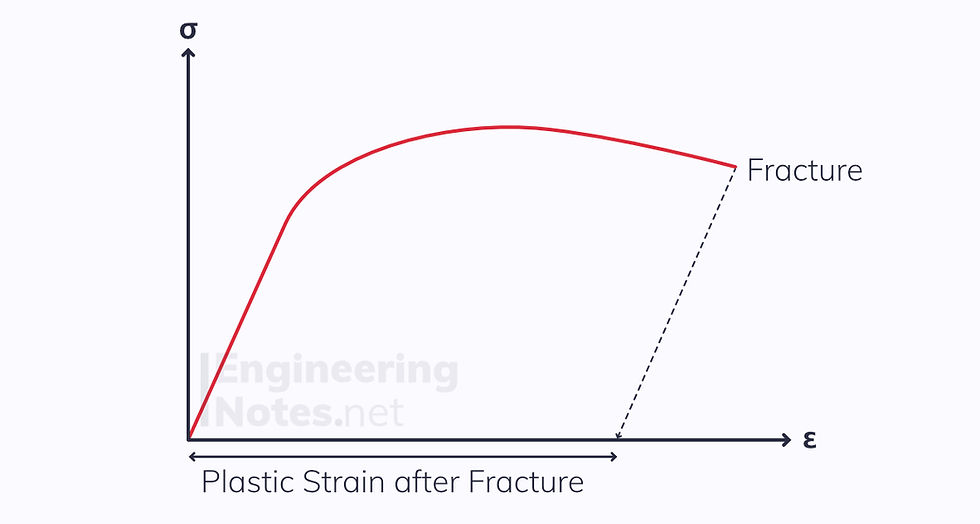

The values for engineering stress and strain are plotted on a stress-strain graph:

This graph is incredibly useful. It tells us:

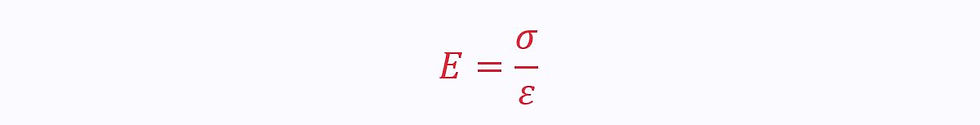

Young’s Modulus, E – The stiffness of the material, given by the gradient of the linear (elastic) region:

Yield Strength, σ(y) – The end of the elastic region, the point where the material starts to deform plastically

Proof Strength, σ(proof) – The stress at a certain strain offset from the yield strength. This offset is defined as a percentage.

Ultimate Tensile Strength, UTS – The maximum stress a material can take without rupture

Deformation & Work Hardening

In the linear region of the stress-strain graph above (up to the yield strength), the material deforms plastically. This means that once the load is removed, the material will return to its initial length and shape.

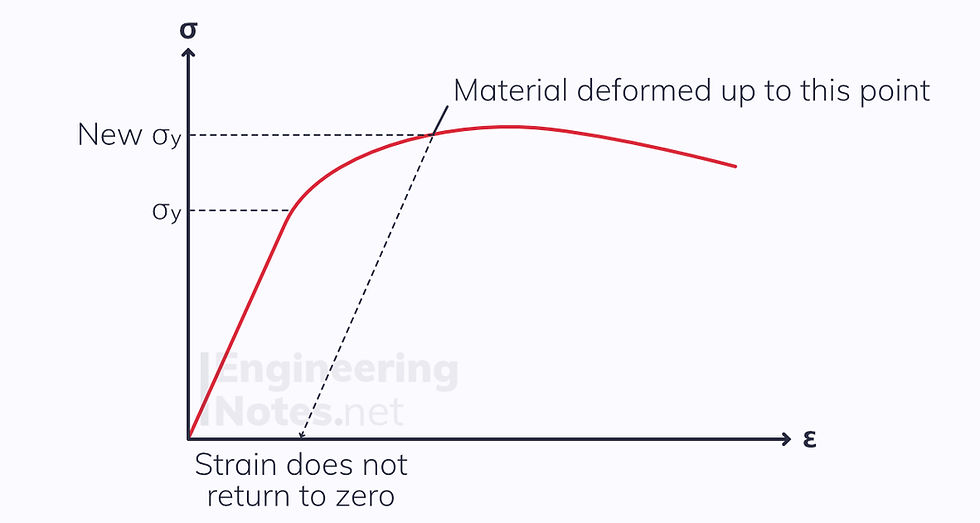

Beyond the yield strength, the graph is curved. This represents the plastic deformation region of the graph, where the material will no longer return to its initial length and shape: it is deformed permanently.

If the material deforms elastically only, once the stress returns to zero (the load is removed), strain also returns to zero.

However, if the material deforms plastically, when the stress returns to zero the strain still has a value. The material now has the same Young’s Modulus, but a higher yield strength, as shown in the graph above. This is known as work hardening.

Poisson’s Ratio

Poisson’s ratio describes how a material changes shape during deformation. It is defined as the ratio of transverse to longitudinal strain:

For most ceramics, ν ≈ 0.2

For most metals, ν ≈ 0.3

For most polymers, ν ≈ 0.4

For uniaxial deformation (where the force is applied in one direction only), the fractional change in volume is given by:

From this we can see that when ν = 0.5, there is no change in volume.

Ductility

Ductility is a measure of how much irreversible strain a material can withstand before fracturing.

It can be defined wither as a percentage of elongation in a tensile test:

Alternatively, it can be defined as the percentage of reduction in area. This is independent of geometry:

Where A is the cross-sectional area, initially (0) and finally (f).

True Stress & Strain

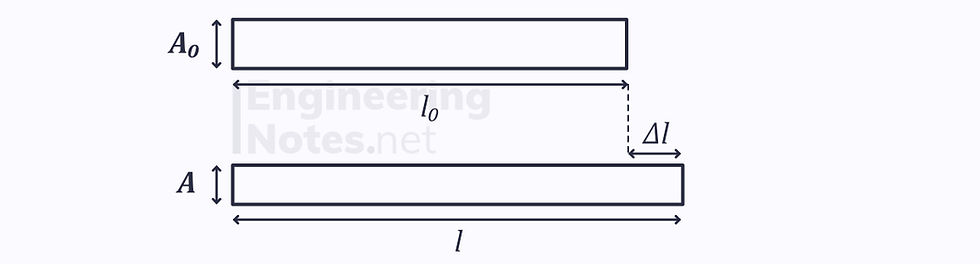

Unlike engineering stress, true stress takes into account the change in cross-sectional area as the material stretches.

In general, engineering stress and strain are good enough approximations for predicting how materials will behave under certain circumstances. However, for very large extensions, this approximation can cause serious errors.

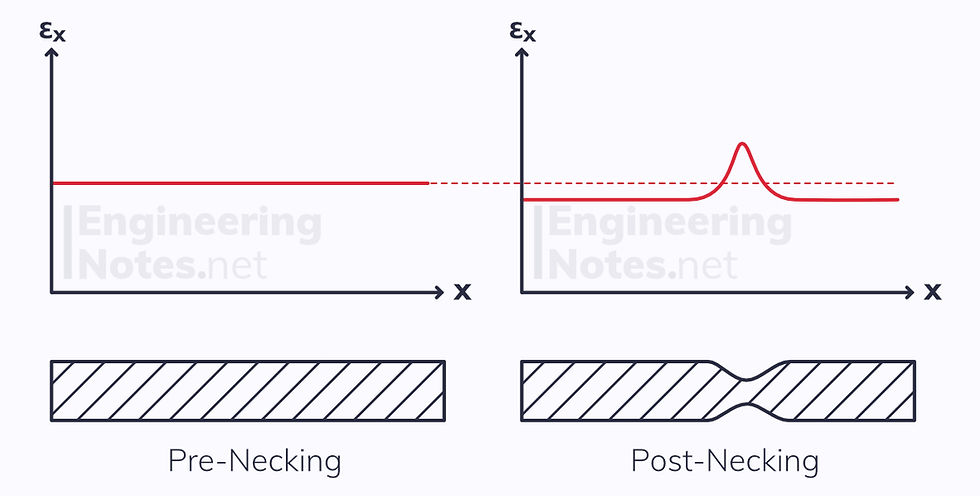

The change in cross-sectional area is particularly significant when necking occurs.

Necking is when a material deforms locally (at a certain point), instead of uniformly.

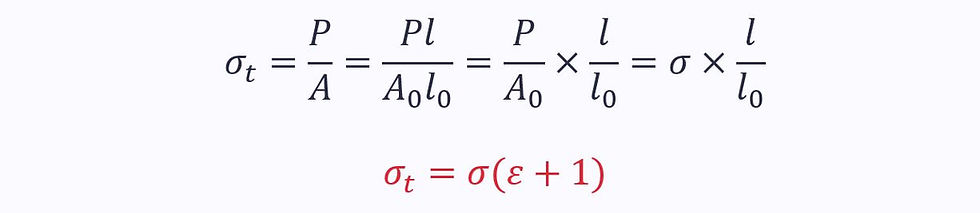

True Stress

While engineering stress decreases after the UTS, true stress continues to rise.

This is because the area continues to decrease, and true stress is defined as:

During elastic deformation, volume is increasing: ν < 0.5

During plastic deformation, volume is constant: ν = 0.5

Therefore, assuming that plastic strain is significantly larger than plastic strain, we take deformation to occur at roughly constant volume.

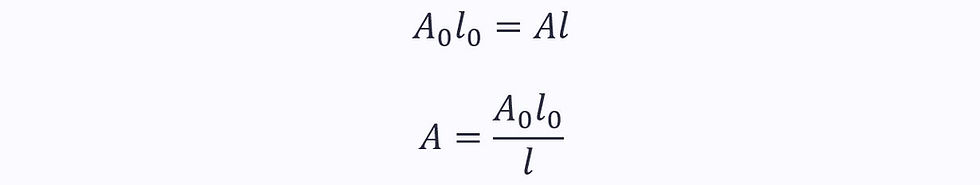

Assuming that volume in the test specimen above is conserved as it extends:

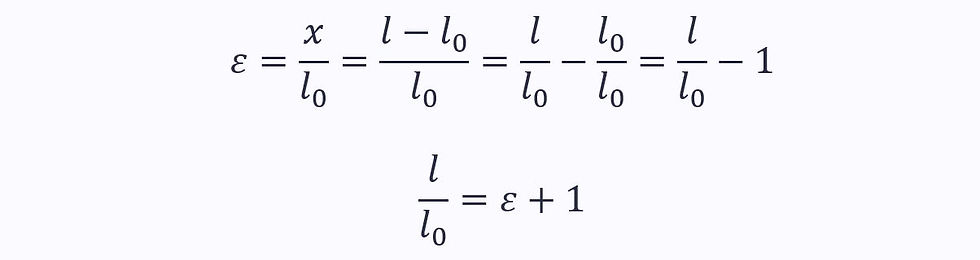

Next, we can rewrite the equation for engineering strain as:

Substituting these into the equation for true stress gives the definition of true stress:

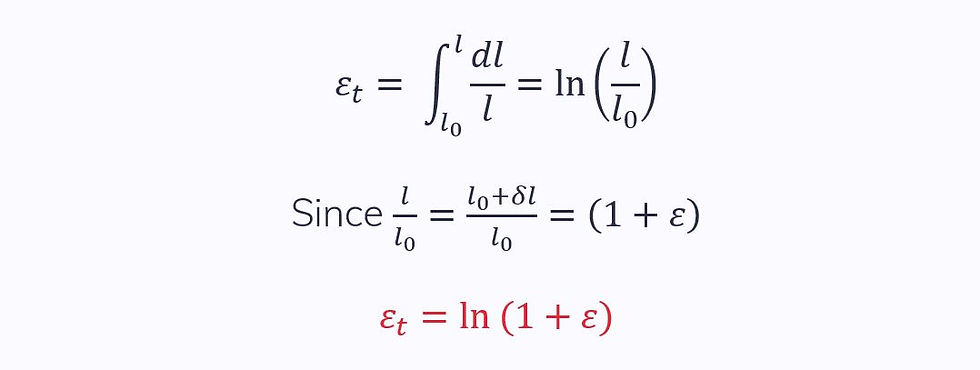

True Strain

True strain considers the constantly changing nature of strain and can be approximated with small values of engineering strain.

Engineering strain is only a valid as an approximation for true strain for values up to 1%

As δl tends to zero, δε gives the true strain:

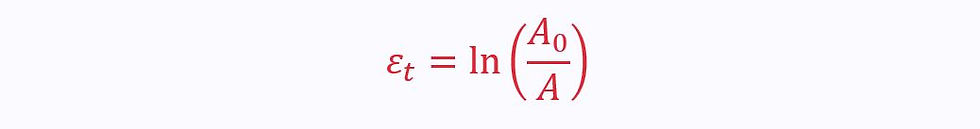

Using the constant volume assumption, we can also define true strain as:

Validity

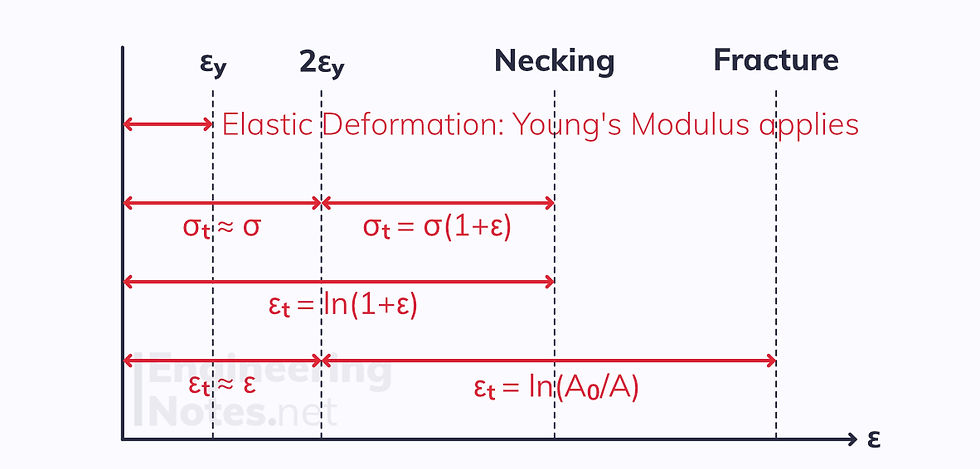

It is important to note that these equations are only valid up to the necking point. This is because after necking, the strain is so much higher at the neck than everywhere else, so it cannot be modelled as uniform:

Engineering stress and strain can be used as an approximation for true stress and strain for small strains: roughly up to twice the yield strength

This chart shows when each equation is valid:

Summary

Materials are generally grouped into four types: metals & alloys, plastics, ceramics & glasses, and composites

Tensile tests are carried out to find the engineering stress-strain properties of a material

These tests give us yield stress, UTS and the Young’s Modulus

Work Hardening is when a material is deformed plastically, raising its yield stress once the load is removed

Poisson’s ratio is the ratio of transverse to longitudinal strain

Ductility is a measure of how much irreversible strain a material can withstand before fracturing

Unlike engineering stress and strain, true stress and strain take into account the change in cross-sectional area of material as it experiences a load

Comments