The Second Law of Thermodynamics

- Engineering

- Nov 10, 2020

- 4 min read

In this notes sheet...

The second law is used for a number of important calculations: finding temperature differences, reversibility, and efficiency of reversible vs irreversible heat engines.

Reversible & Irreversible Processes

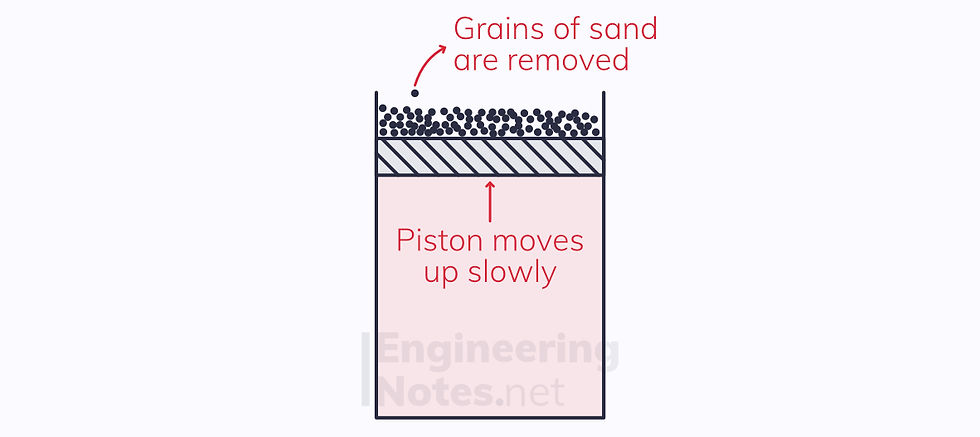

Let us take the classic example of a quasi-equilibrium expansion:

If the mass on the piston is made up of a vast number of minuscule weights, like sand, removing a single grain pushes the piston up ever so slightly. The change is so small, that the return to equilibrium is almost instant.

For each grain of sand removed, we have an additional point on the P-V diagram – as pressure decreases, volume increases.

This process is reversible

It is reversible, because if we return the grains of sand one at a time, the piston will move down by the same amount. We neglect friction or leakage.

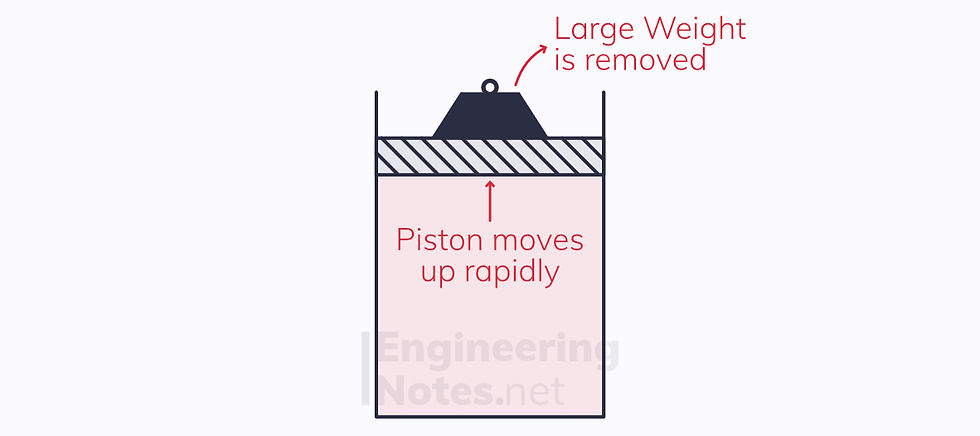

If, however, the weight consist of one large mass, and this is removed, the process is not in quasi-equilibrium.

The process is irreversible

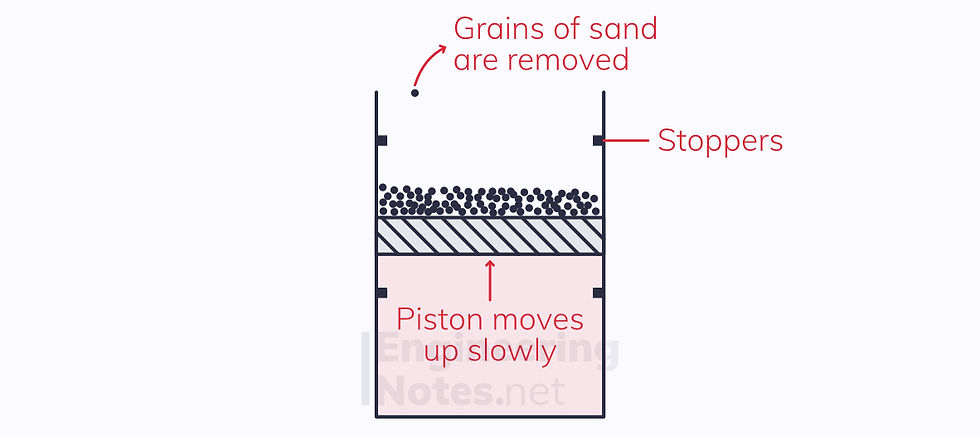

In this example, the expansion itself is quasi-equilibrium, as we have returned to the grains of sand. However, when the piston hits the top or bottom stoppers, it makes a sound, releasing energy. This energy cannot be gotten back, so

The process is irreversible

What makes a process irreversible?

Friction

Unresisted expansion

Heat transfer to surroundings

Combustion

Mixing of different fluids

Clearly, then, the majority of real-life processes are irreversible.

The Second Law

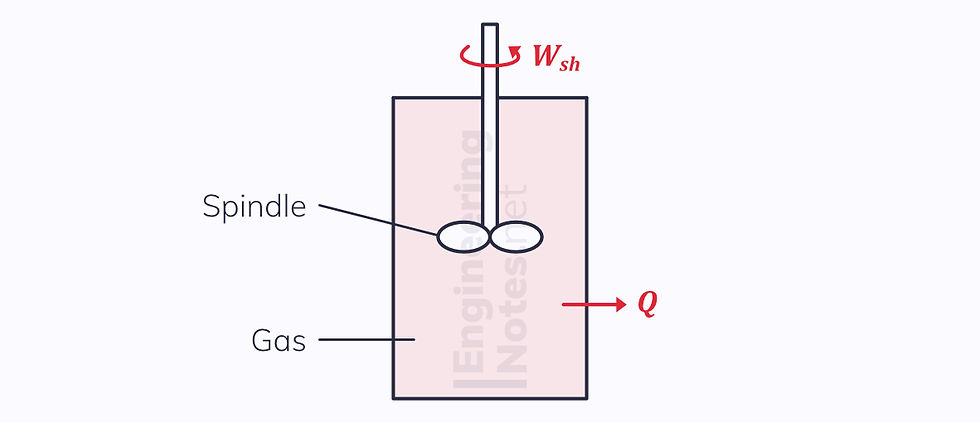

Take the example of a spindle rotating in a container:

Spindle rotates

Gas in container heats up

Heat from gas is conducted through container and heats up the surroundings

If we reverse this:

Surroundings are heated

Gas inside container heats up

Spindle does not start rotating

We know from experience that this is the case, but why?

This is where the second law comes in:

Heat cannot be transferred from a cold body to a hotter body without a work input.

This is the all-important idea of direction: some things are allowed backwards as well as forwards, but many things are only allowed forwards.

Heat Engines & Efficiency

A heat engine is a device that connects a hot and cold reservoir with a work input or output.

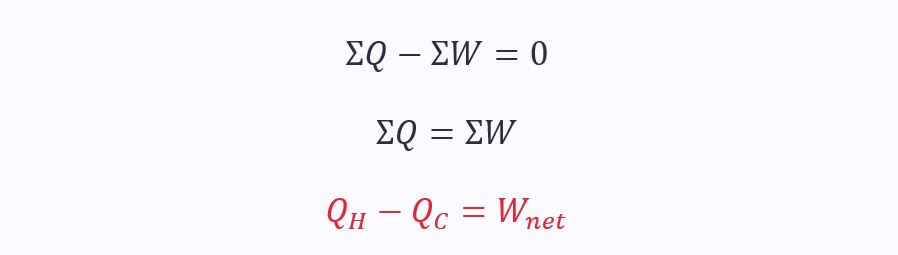

From the first law:

The second law is often also used to describe efficiency, η:

Using the equation from the first law above, the efficiency can also be written as:

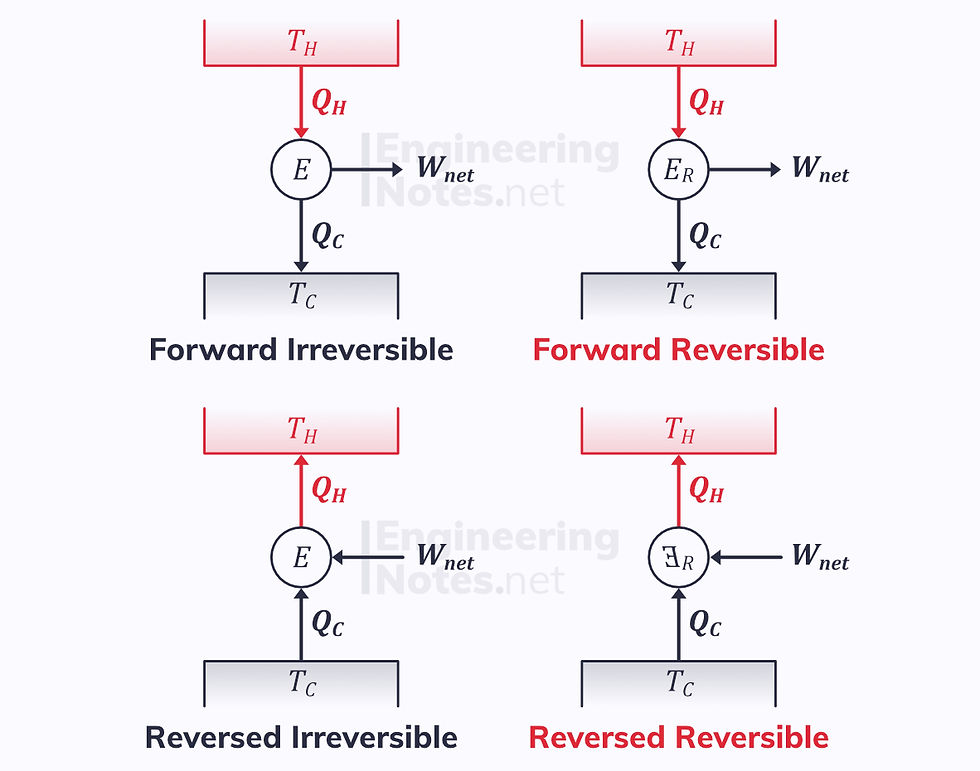

Reversed Engine

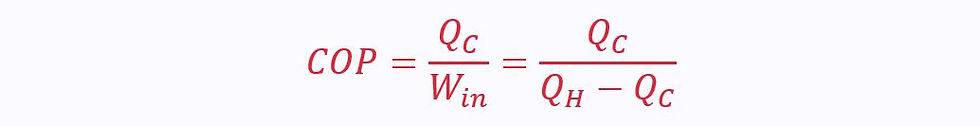

For a reversed engine, like a refrigerator, work is the input not the output. The efficiency it known as the ‘Coefficient of Performance’ (COP).

In a fridge, the output is the cold reservoir, so COP is given as:

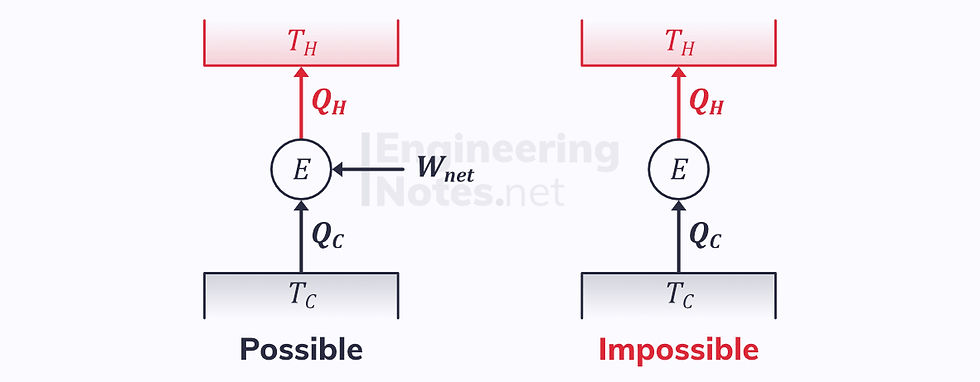

Clausius’ Statement

The Clausius statement of the second law tells us that it is only possible to reverse a heat engine if there is a net work input from its surroundings:

A reversible engine is always more efficient than an irreversible engine.

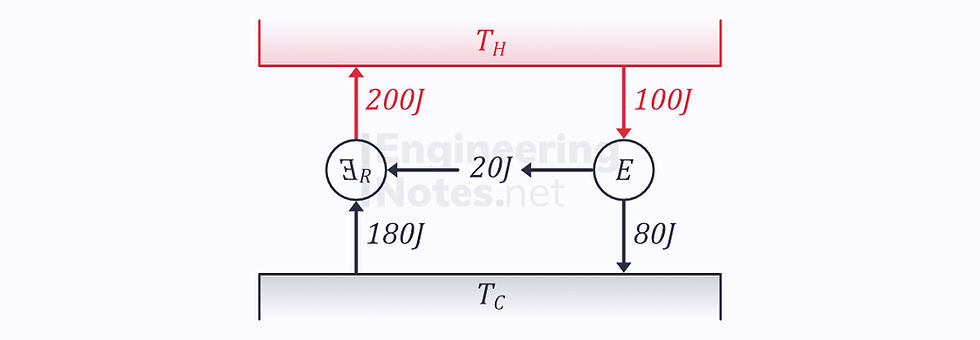

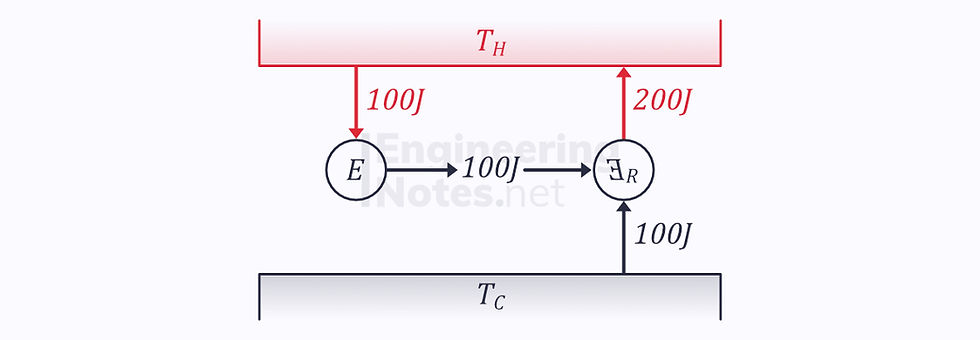

We can prove this by contradiction: if we take two engines, one reversible and one irreversible, and assume that the former has an efficiency of 10% and the latter 20%:

If we now reverse the reversible engine:

Modelling both engines as a single control volume:

According to the Clausius statement, this is impossible.

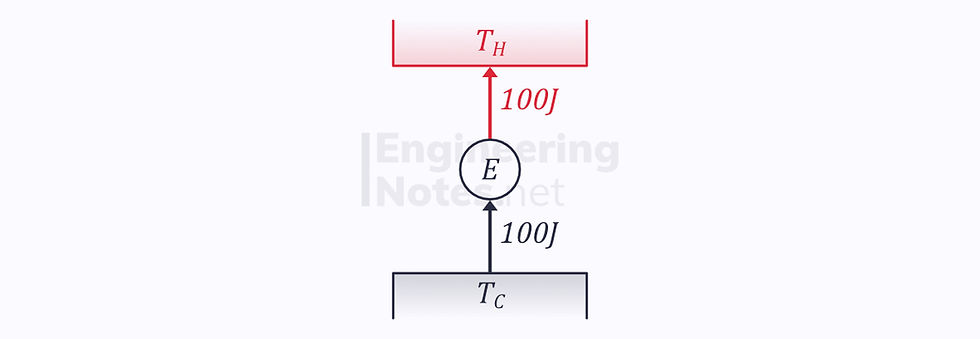

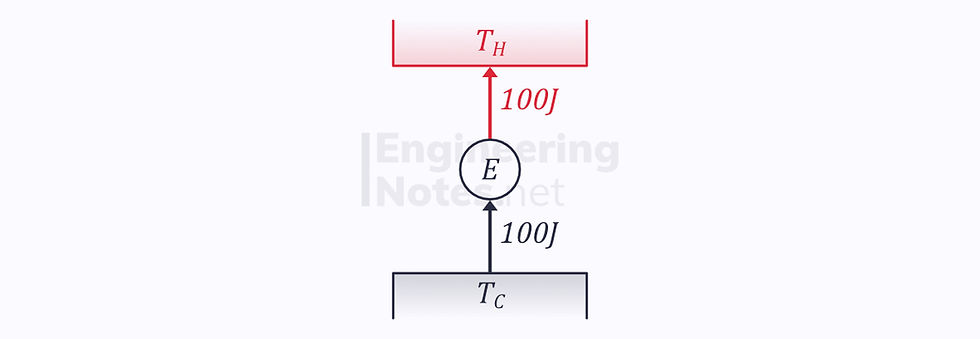

Similarly, we can use Clausius’ statement to show the 100% efficient engines are impossible:

You cannot have an E100 engine

Taking a 100% efficient engine and connecting its output to a reversed engine looks like this:

Modelling these two engines as one control volume once again violates the Clausius statement:

This is summarised by the Kelvin-Planck statement:

No heat engine can deliver a work output equivalent to the heat input from a single reservoir.

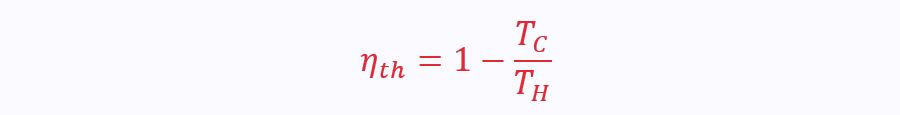

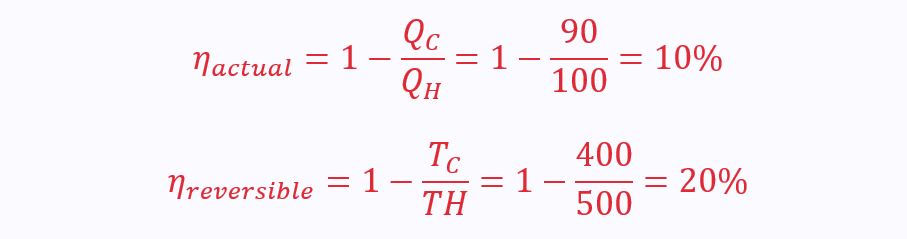

Actual vs Ideal Efficiencies

Since no heat engine can be 100% efficient, it is often unhelpful to talk about an engine’s actual efficiency. Instead, when talking about its performance, we compare its efficiency to that of its ideal (reversible) counterpart:

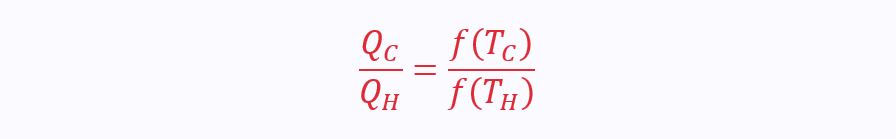

The efficiency of a reversible engine is a function of the temperatures between which the engine operates. This leads to the equation:

This is due to the absolute temperature scale, as defined by Kelvin: the scale that sets the triple point of water (0°C) as 273.16 K. This scale is identical to the ideal gas temperature scale, from which the relationship Pv=RT is derived. This can be reworked to show that for a reversible engine, heat is a function of temperature.

Therefore:

Since the increment of the scale is 1 K, this simply becomes:

Remember this is only the case for ideal, reversible engines.

There is a huge difference in the actual efficiency of a heat engine and its efficiency compared to the maximum achievable efficiency from its reversible counterpart:

The actual efficiency appears to be only 10%, but really it is 50%:

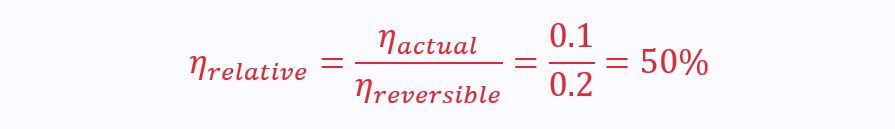

Reversed Engine

Back to the fridge example, the ideal Coefficient of Performance (COP) for a reversible reversed engine is given as a function of the temperatures, not heats:

Improving Efficiency

As you can probably tell from the numbers in the example above, efficiencies of heat engines can often be quite low. Therefore, there is a constant push to increase this to boost the performance of a system, to make it more economical, or to make it more environmentally friendly.

There are a few key ways of boosting a heat engine’s efficiency:

Find a lower temperature cold reservoir

This is difficult, however. Generally, rivers, lakes or the ocean are used for cold reservoirs, but these are rarely lower than around 10 °C

Increase the temperature of the hot reservoir

Increasing the temperature difference between the two reservoirs increases the maximum possible efficiency

Minimise losses

Insulation, less friction etc. brings the actual engine closer to its reversible counterpart

Find a use for the losses

Can you use the output heat for a practical purpose, such as heating?

Generally, this is difficult because the cold reservoir is around 20 °C, which is not helpful for anyone.

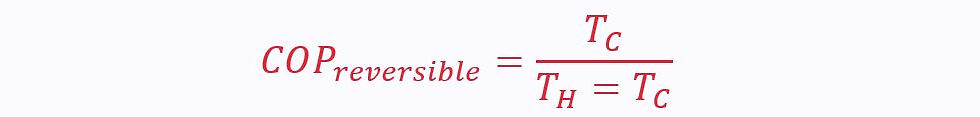

Carnot Cycle

The Carnot cycle is an unobtainable, ideal cycle of compression and expansion. An ideal petrol piston engine can be modelled as a Carnot engine.

It consists of four stages:

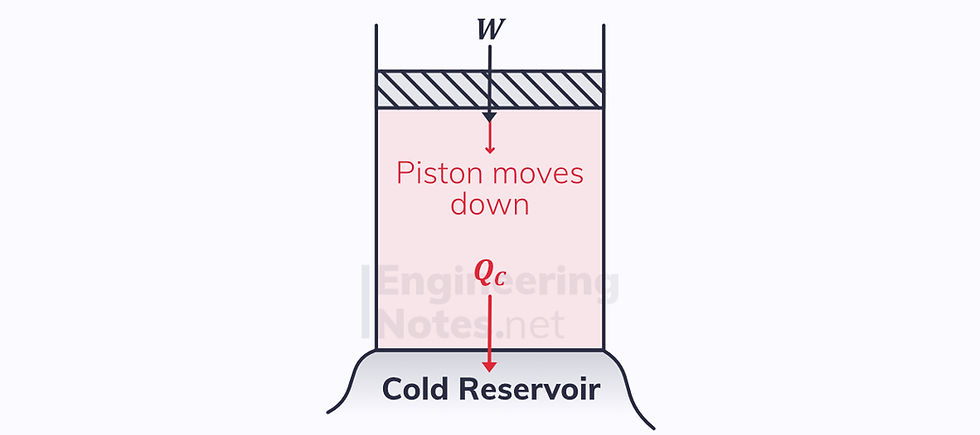

1) Isothermal Compression

There is a heat output

Since the process is isothermal, there is no change in internal energy. Therefore, according to the first law, ΔQ = ΔW

The piston moves down

The temperature does not change, so T₁ = T₂, which equals the cold reservoir temperature

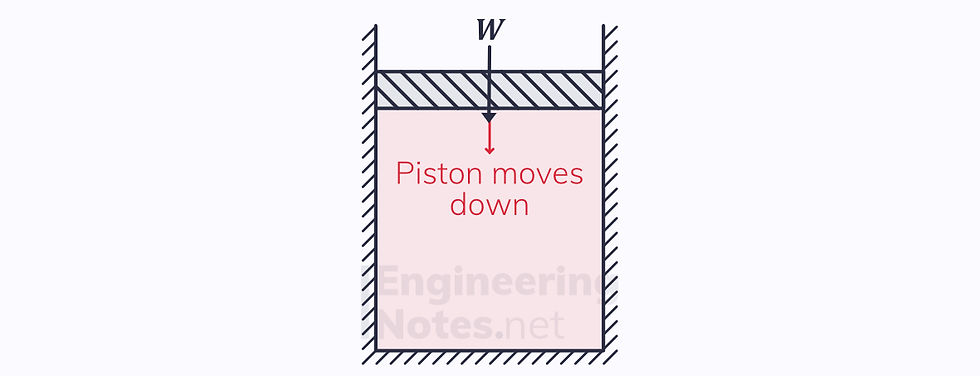

2) Adiabatic Compression

There is a work input

Adiabatic, so first law becomes -ΔW = ΔU

The piston still moves down

T₃ = the hot reservoir temperature

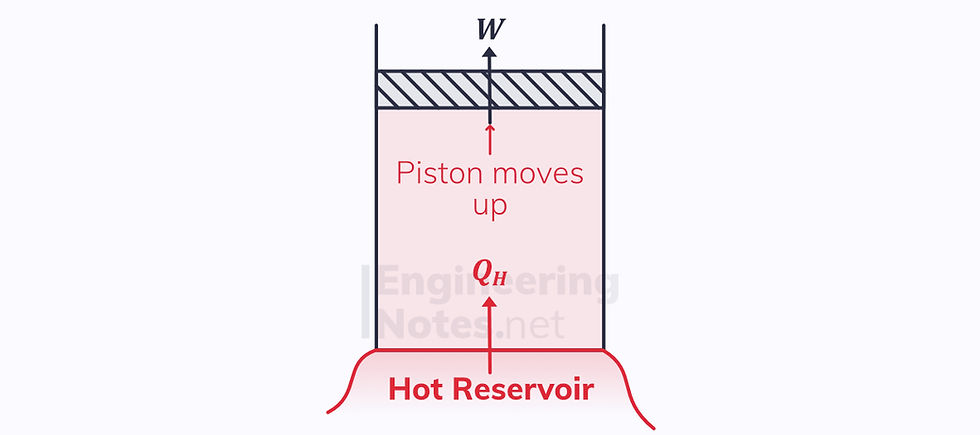

3) Isothermal Expansion

There is a heat input

Isothermal, so ΔQ = ΔW

The piston moves up

T₃ = T₄ = hot reservoir temperature

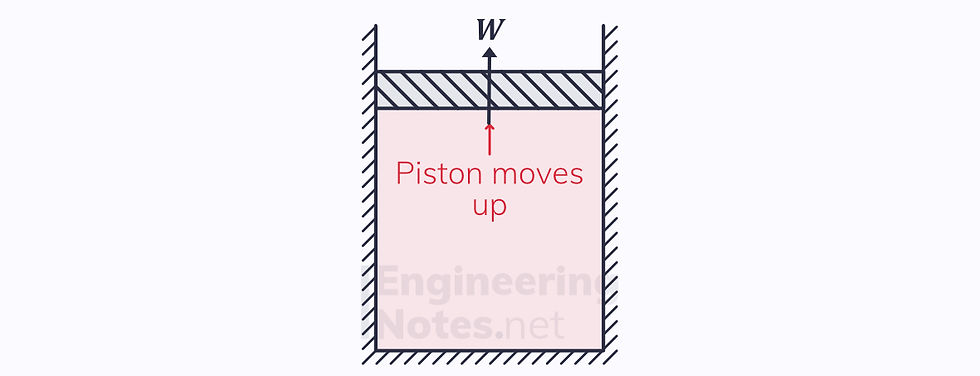

4) Adiabatic Expansion

There is a work output

Adiabatic, so first law becomes -ΔW = ΔU

The piston continues to move up

T₁ = T₂ = the cold reservoir temperature

All four processes are fully reversible

Comments